Of course there’s no strict delineation between these different “levels.” They’re just convenient labels for us to talk and reason about them. In reality the brain is a tangled mess of agents operating on many different levels, often simultaneously; in Hofstadter’s phrase, it’s a heterarchy rather than a hierarchy.

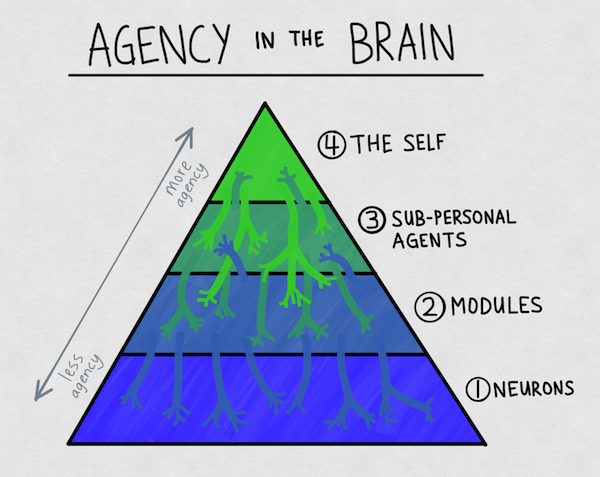

An agent is an entity capable of autonomous, intelligent, goal-directed behavior. But agency isn’t binary; it’s not something you either ‘have’ or ‘don’t have.’ Instead it admits of degrees. The more autonomous, intelligent, adaptive, and purposeful a system is, the more agency we will attribute to it.

Agency is a way of describing a system at the level of abstraction that includes goals, obstacles, motivations, etc. If you look too closely (at a sufficiently low level of abstraction), the agency might seem to disappear. A plant, for example, is ‘merely’ growing its stem according to the concentration of auxin, just like we (humans) are often ‘merely’ acting on our drives and instincts. But zoom back out, and once again it will be productive to describe the system at the agent-level of abstraction. Thus explanatory power, not free will, is the hallmark of agency.

Not only is agency the function of the brain — and thus it’s very reason for existence — but it’s also built into the brain’s fabric and architecture. Because even Neurons have agency, in the form of (metabolic) selfishness, higher-order brain systems don’t need to create agency ‘from scratch’ out of mindless robotic slaves. They inherit agency pretty much for free.

The brain is thus uniquely hospitable to agents, who can be said to take root and grow in the brain quite readily.

The basic idea is that there’s a level of abstraction where we can describe the brain in terms of hundreds, thousands, or even millions of little modules, more or less independent of each other, each with its own functional purpose or goal.

At the level above simple modules, but below the self, are poised what I will call sub-personal agents. These are systems like drives or instincts — hunger, lust, curiosity, greed, addictions — that have agency recognizable even to lay-people. We don’t need neuroscience to reason about these agents because we can ‘feel’ them, through introspection, pulling at our psyches — faintly or insistently, gently or violently.

Sub-personal agents aren’t capable of using language directly (like the self is), so their agency is limited and less outward-facing. But they nevertheless have real power, in that they’re capable of influencing the cognition, emotions, and behavior of the human creatures they inhabit. They’re also capable of co-opting the reasoning process to justify their desires.

When you take an addictive drug for the first time — nicotine, let’s say — a new agent begins to bud around that source of pleasure (i.e., the neurotransmitters that flood your brain while smoking). The agent starts out small and weak. But the more you feed it, the bigger it grows, until there are many neurons, many modules, and even other brain-agents under its influence, feeding off the nicotine and craving it in ever larger doses, co-opting your planning and reasoning skills so it can scheme about how to get more of it.

This process, of course, is extremely adaptive for us, as evolved organisms — but only when the pleasure corresponds to something of survival or reproductive value: food, sex, social status, mastery of physical skills. The fact that our brains are capable of growing agents dedicated to pursuing food and sex is essential to our survival. It’s only in the modern (super-stimulating) environment that we get into trouble.

Kevin Simler, One Brain, Many Selves: Demons, Tulpas, and Neurons Gone Wild, 2014

Machiavelli, the founder of political science, spoke of his imaginary friends. When he was exiled to rural Italy after decades as a political insider, he was lonely by day; imaginarily popular at night:

“When evening comes, I return home and go into my study. On the threshold I strip off my muddy, sweaty, workday clothes, and put on the robes of court and palace, and in this graver dress I enter the antique courts of the ancients and am welcomed by them, and there I taste the food that alone is mine, and for which I was born. And there I make bold to speak to them and ask the motives of their actions, and they, in their humanity, reply to me. And for the space of four hours I forget the world, remember no vexation, fear poverty no more, tremble no more at death: I pass indeed into their world.”

Dr. Jeremy E. Sherman, Adults Have Imaginary Friends, Too, 2013

A person, like a society, is composed of parts with their own private agendas, all taking part in a continuously renegotiated dance of conflict, cooperation, and compromise. Our disparate motivations are like politicians trying to advance a faction, and the self, such as it is, is **something like a prime minister — not powerful in its own right, but because it has managed to become the public face for the most powerful faction**.

In this view, the self is the loudest of the social Agents. It’s both externally- and internally-facing, its role as much public relations as executive control.

In other words, the self may be less of a feature of our brains (planned or designed by our genes), and more of a growth. Every normal human brain placed in the right environment — with sufficient autonomy and potential for social interaction — will grow a self-agent. But if the brain or environment is abnormal or wrong (somehow) or simply different, the self may not turn out as expected.

Imagine a girl raised from infancy in the complete absence of socializing/civilizing contact with other people. The resulting adult will almost certainly have a self concept, e.g., will be able to recognize herself in the mirror. But without language, norms, shame, and social punishment, the agent(s) at the top of her brain hierarchy will certainly not serve a social/PR role. She’ll have no ‘face’, no persona. She’ll be an intelligent creature, yes, but not a person.

In this way, the self takes on a structure that depends on (and reflects) the environment it’s raised in.

Kevin Simler, One Brain, Many Selves: Demons, Tulpas, and Neurons Gone Wild, 2014

See Also: Turtles All The Way Down, Internal Family Systems, Plurality