What is an Agent?

The mind and self are not monolithic entities.

Have you ever done something that surprised you, said something you didn’t mean to, or been torn apart by conflict inside yourself? Have you ever contradicted yourself or disagreed with your own opinions? Most folks have at some point. It’s normal to be complicated.

People are layers of thoughts, feelings, memories, behaviors, and other patterns stacked on top of each other. If modern neuroscience has any truth to it, then these things can be traced back to specific neural pathways: this part of your brain responds in this situation, this other part handles this action. In a simple world, only one pathway would ever be active at a time. In reality, many patterns are activated as a part of life, and sometimes these patterns conflict with each other.

It can be helpful to understand these patterns as being intelligent entities with a degree of autonomy in achieving their goal. We can call these entities agents.

An agent is a cluster of self-stuff that exhibits apparent autonomy and awareness. They often act in service of a specific goal. You may have an agent that’s responsible for getting you food when you’re hungry, for example, or people pleasing when a social threat arises.

If you’re a tech nerd, think of agents as being the individual hardware components of a computer. The GPU handles a particular kind of calculation. The CPU handles a different area of computation. RAM stores data temporarily. The PSU keeps everything else running. So on and so forth. All of these pieces create a computer, but they’re also their own entities with their own goals and activities within that computer.

Agents are Shaped

Agents are shaped by the environments they develop in. If placed in an environment that demands people pleasing to stay safe, then a person will likely develop a very skilled people-pleasing agent to survive in that environment. Another person may have grown up in an environment where appealing to people only got them hurt. They may have a skilled agent focused on self-sufficiency instead of people pleasing.

Most people develop in different environments from each other. Even in the same environment, small differences in experiences can compound to shape agents in different ways. As a result, every person will have at least minor differences in what their agents’ goals are, as well as which agents hold the most power inside them.

Agents Interact

Every agent has a goal of some sort. Sometimes, these goals are compatible, and agents may work together to accomplish them. They may make a truce in which they alternate working towards each other’s goals, or they may find a common target to work towards that satisfies both agents’ goals.

Just as often, goals conflict. In these cases, agents may learn that they can best achieve their goals by sabotaging, manipulating, and betraying each other. Sometimes, this leads to stalemates in which neither goal can be accomplished.

From the overarching self’s perspective (if there is one), a conflict between agents looks like self-sabotage, careless mistakes and slips, losing focus or motivation, getting stuck in harmful behaviors, or otherwise acting in ways that surprise or upset that self. Freudian slips are a strong example of one agent acting against the wishes of another. “I didn’t mean to say that, I don’t know where that came from.”

These conflicts can be resolved, but doing so requires de-escalating any existing conflicts, then finding a way for all agents involved to work towards their goals. There’s arguably a separate optimization problem here around the best way to balance these goals (alternate between them equally regardless of benefit, pick the moment’s goals depending on which goal could gain the most benefit, change an agent’s goals to an equally agreeable alternative, find common targets- even then, what targets?), but the essence of it lies in solving those conflicts.

Layers of Agency

Agents can be composed of other agents. As a possible example, eating food is a complicated task. Once you have food in your mouth, you have to chew it, decide how you feel about it, detect any threats (this milk tastes sour), and so on. The “eat food” agent might be composed of other agents that handle each piece of this pattern.

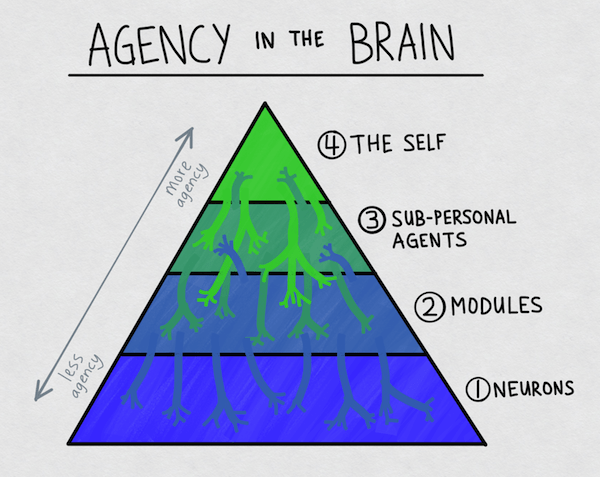

The further down you go, the simpler these agents get. Top-level agents are composed of many smaller agents, and they can exhibit complex behaviors to reach their goals. They might manipulate, befriend, or sabotage other agents, for example. Subagents are parts of larger agents. They tend to have more specific goals and more limited behavioral patterns; while this limits the apparent complexity of their behavior, it does allow them to optimize much more effectively for their goal, as they have a narrower scope to worry about.

The self itself is an agent. It might be the sole top-level agent, or it might be one of many, but it tends to be the most complex, powerful, or social-facing agent. Just like any other agent, it was shaped by the environment and works towards its own goals.

See also: Internal Family Systems, Parts

Of course there’s no strict delineation between these different “levels.” They’re just convenient labels for us to talk and reason about them. In reality the brain is a tangled mess of agents operating on many different levels, often simultaneously; in Hofstadter’s phrase, it’s a heterarchy rather than a hierarchy.

An agent is an entity capable of autonomous, intelligent, goal-directed behavior. But agency isn’t binary; it’s not something you either ‘have’ or ‘don’t have.’ Instead it admits of degrees. The more autonomous, intelligent, adaptive, and purposeful a system is, the more agency we will attribute to it.

Agency is a way of describing a system at the level of abstraction that includes goals, obstacles, motivations, etc. If you look too closely (at a sufficiently low level of abstraction), the agency might seem to disappear. A plant, for example, is ‘merely’ growing its stem according to the concentration of auxin, just like we (humans) are often ‘merely’ acting on our drives and instincts. But zoom back out, and once again it will be productive to describe the system at the agent-level of abstraction. Thus explanatory power, not free will, is the hallmark of agency.

Not only is agency the function of the brain — and thus it’s very reason for existence — but it’s also built into the brain’s fabric and architecture. Because even Neurons have agency, in the form of (metabolic) selfishness, higher-order brain systems don’t need to create agency ‘from scratch’ out of mindless robotic slaves. They inherit agency pretty much for free.

The brain is thus uniquely hospitable to agents, who can be said to take root and grow in the brain quite readily.

The basic idea is that there’s a level of abstraction where we can describe the brain in terms of hundreds, thousands, or even millions of little modules, more or less independent of each other, each with its own functional purpose or goal.

At the level above simple modules, but below the self, are poised what I will call sub-personal agents. These are systems like drives or instincts — hunger, lust, curiosity, greed, addictions — that have agency recognizable even to lay-people. We don’t need neuroscience to reason about these agents because we can ‘feel’ them, through introspection, pulling at our psyches — faintly or insistently, gently or violently.

Sub-personal agents aren’t capable of using language directly (like the self is), so their agency is limited and less outward-facing. But they nevertheless have real power, in that they’re capable of influencing the cognition, emotions, and behavior of the human creatures they inhabit. They’re also capable of co-opting the reasoning process to justify their desires.

When you take an addictive drug for the first time — nicotine, let’s say — a new agent begins to bud around that source of pleasure (i.e., the neurotransmitters that flood your brain while smoking). The agent starts out small and weak. But the more you feed it, the bigger it grows, until there are many neurons, many modules, and even other brain-agents under its influence, feeding off the nicotine and craving it in ever larger doses, co-opting your planning and reasoning skills so it can scheme about how to get more of it.

This process, of course, is extremely adaptive for us, as evolved organisms — but only when the pleasure corresponds to something of survival or reproductive value: food, sex, social status, mastery of physical skills. The fact that our brains are capable of growing agents dedicated to pursuing food and sex is essential to our survival. It’s only in the modern (super-stimulating) environment that we get into trouble.

Kevin Simler, One Brain, Many Selves: Demons, Tulpas, and Neurons Gone Wild, 2014

Realize that every human cell in your body, including your neurons, is a direct descendent of eukaryotic cells that lived and fended for themselves, for about a billion years, as free-swimming, free-living little agents. They had to develop an awful lot of know-how and self-protective talent to do that. But when they joined forces to become multi-cellular creatures, they gave up a lot of that. They became, in effect, domesticated — part of larger, more monolithic organizations.

In general, we don’t have to worry about our muscle cells rebelling against us. (When they do, we call it cancer.) But in the brain, I think, some little switch has been thrown in the genetics that, in effect, makes our neurons a little bit feral. It’s like what happens when you let sheep or pigs go feral: they recover their wild talents very fast.

Maybe the neurons in our brains are not just capable, but motivated, to be more adventurous, exploratory, or risky in the way they live their lives. They’re struggling amongst themselves for influence and for staying alive. As soon as that happens, you have room for cooperation, to create alliances, coalitions, cabals, etc.

Mike Merzenich sutured a monkey’s fingers together so that it didn’t need as much cortex to represent two separate individual digits, and pretty soon the cortical regions that were representing those two digits shrank, making that part of the cortex available to use for other things. When the sutures were removed, the cortical regions soon resumed pretty much their earlier dimensions.

Or if you blindfold yourself for eight weeks, as Alvaro Pascual-Leone does in his experiments, you find that your visual cortex starts getting adapted for Braille, for haptic perception, for touch.

Why should these idle neurons be so eager to pitch in? Well, they’re out of work. They’re unemployed, and if you’re unemployed, you’re not getting your neuromodulators, so your receptors are going to start disappearing, and pretty soon you’re going to be really out of work, and then you’re going to die.

Kevin Simler, One Brain, Many Selves: Demons, Tulpas, and Neurons Gone Wild, 2014

A person, like a society, is composed of parts with their own private agendas, all taking part in a continuously renegotiated dance of conflict, cooperation, and compromise. Our disparate motivations are like politicians trying to advance a faction, and the self, such as it is, is **something like a prime minister — not powerful in its own right, but because it has managed to become the public face for the most powerful faction**.

In this view, the self is the loudest of the social Agents. It’s both externally- and internally-facing, its role as much public relations as executive control.

In other words, the self may be less of a feature of our brains (planned or designed by our genes), and more of a growth. Every normal human brain placed in the right environment — with sufficient autonomy and potential for social interaction — will grow a self-agent. But if the brain or environment is abnormal or wrong (somehow) or simply different, the self may not turn out as expected.

Imagine a girl raised from infancy in the complete absence of socializing/civilizing contact with other people. The resulting adult will almost certainly have a self concept, e.g., will be able to recognize herself in the mirror. But without language, norms, shame, and social punishment, the agent(s) at the top of her brain hierarchy will certainly not serve a social/PR role. She’ll have no ‘face’, no persona. She’ll be an intelligent creature, yes, but not a person.

In this way, the self takes on a structure that depends on (and reflects) the environment it’s raised in.

Kevin Simler, One Brain, Many Selves: Demons, Tulpas, and Neurons Gone Wild, 2014

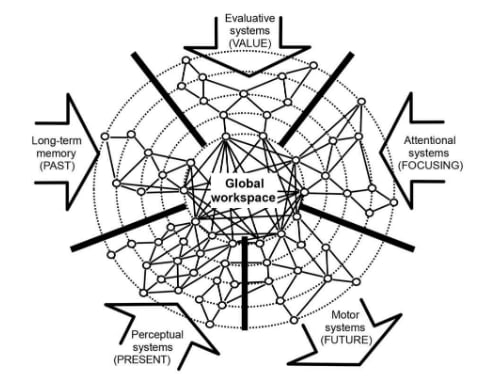

One of the main ideas of the multiagent model is that the brain contains a number of different subsystems operating in parallel, each focusing on their own responsibilities. They share information on a subconscious level, but also through conscious thought. The content of consciousness roughly corresponds to information which is being processed in a “global workspace” - a “brain web” of long-distance neurons, which link multiple areas of the brain together into a densely interconnected network.

The global workspace can only hold a single piece of information at a time. At any given time, multiple different subsystems are trying to send information into the workspace, or otherwise modify its contents. Experiments show that a visual stimuli needs to be shown for about 50 milliseconds for it to be consciously registered, suggesting that the contents of consciousness might be updated at least 20 times per second. Whatever information makes it into consciousness will then be broadcast widely throughout the brain, allowing many subsystems to synchronize their processing around it.

The exact process by which this happens is not completely understood, but involves a combination of top-down mechanisms (e.g. attentional subsystems trying to strengthen particular signals and keep those in the workspace) as well as bottom-up ones (e.g. emotional content getting a priority). For example, if you are listening to someone talk in a noisy restaurant, both their words and the noise are bottom-up information within the workspace, while a top-down process tries to pick up on the words in particular. If a drunk person then suddenly collides with you, you are likely to become startled, which is a bottom-up signal strong enough to grab your attention (dominate the workspace), momentarily pushing away everything else.

There is also a constant learning process going on, where the brain learns which subsystems should be given access in which circumstances, while the subsystems themselves also undergo learning about what kind of information to send to consciousness.

Kaj_Sotala, 2018, A non-mystical explanation of insight meditation and the three characteristics of existence: introduction and preamble

See Also: Turtles All The Way Down, Comparison of Frameworks