Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID) is a pathologic presentation of Plurality.

For those who find psychiatry’s framework helpful, DID provides a label and lens for working with heavily dissociated Parts (also called alters).

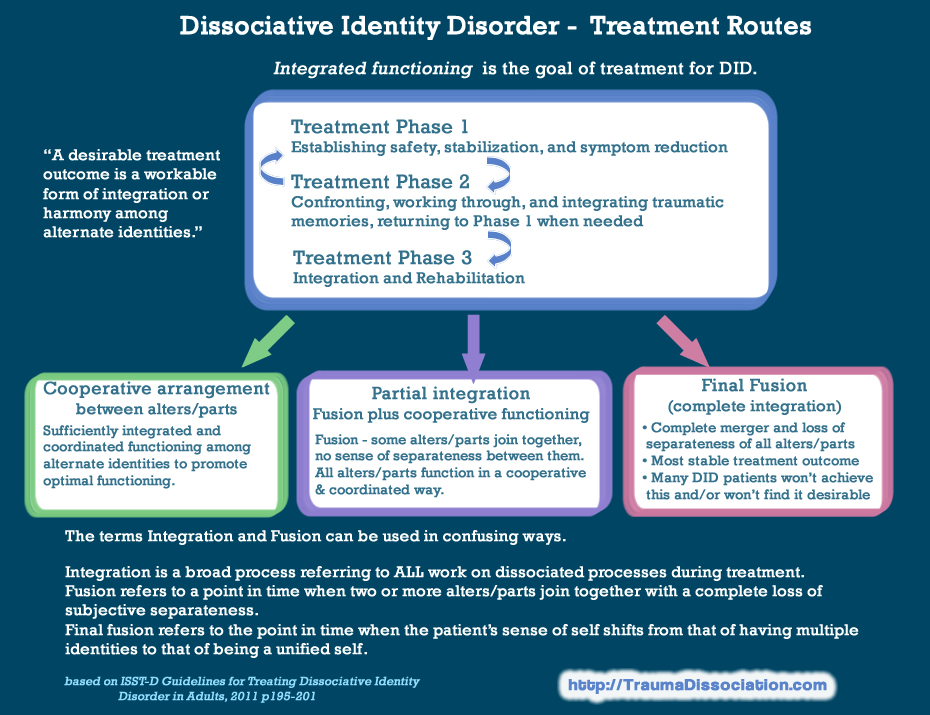

The diagnosis of DID provides a treatment track:

- get to know your alters and build coping skills,

- process trauma,

- and either fuse or learn to get along with each other.

DID is not the only way to view Plurality, but it can be a helpful framework within psychiatry to get support in cases where Parts are so heavily separated from each other that they can’t share memories, skills, etc. with each other, or where the system is unable to cooperate with itself to live life.

What is Dissociative Identity Disorder?

Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID) is characterized by the presence of two or more separate personality states (dissociative identities), accompanied by gaps in personal agency and sense of self. This means that the person experiencing DID has the impression that certain thoughts, actions, and emotions don’t belong to them, as they are sourced from another distinct identity.

You may see DID referred to as Multiple Personality Disorder or Split Personality Disorder. These terms are outdated and inaccurate, as DID is a dissociative disorder, not a personality disorder. The new term came into use in 1994.

People with DID describe their experiences in a variety of ways. Some see themselves as multiple people or entities coexisting within one body, while others view themselves as a person composed of independent parts or sides. Dissociative identities may be called alters, parts, headmates, friends, voices, and more. Some people with DID use the term system to describe themselves collectively.

Each identity within a DID system has a unique experience of the world and distinct relationships with self, body, external individuals, and the environment. This comes with differences in thinking, feeling, moving, sensing, understanding, and interacting. Identities may be experienced covertly through intrusions of feelings, thoughts, and sensations that don’t feel like they belong to the individual. They can also be experienced overtly as different identities taking control of consciousness and functioning, also known as switching.

DID often involves experiences of amnesia, which can include the inability to recall traumatic events, the recent past, daily life details, or the activities of different alters. Amnesia is a diagnostic requirement according to the American Psychiatric Association (APA), but it is not included in the World Health Organization (WHO) definition of DID. Even without total amnesia, people with dissociative identities often feel a lack of ownership of particular memories, as if the remembered event happened to somebody else.

Multiplied By One, What is Dissociative Identity Disorder, or DID?

DSM-5 Criteria

A) Disruption of identity characterized by two or more distinct personality states, which may be described in some cultures as an experience of possession. The disruption in identity involves marked discontinuity in sense of self and sense of agency, accompanied by related alterations in affect, behavior, consciousness, memory, perception, cognition, and/or sensory-motor functioning. These signs and symptoms may be observed by others or reported by the individual.

B) Recurrent gaps in the recall of everyday events, important personal information, and/ or traumatic events that are inconsistent with ordinary forgetting.

C) The symptoms cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.

D) The disturbance is not a normal part of a broadly accepted cultural or religious practice. Note: In children, the symptoms are not better explained by imaginary playmates or other fantasy play.

E) The symptoms are not attributable to the physiological effects of a substance (e.g., blackouts or chaotic behavior during alcohol intoxication) or another medical condition (e.g., complex partial seizures).

Diagnostic Features

The defining feature of dissociative identity disorder is the presence of two or more distinct personality states or an experience of possession (Criterion A). The overtness or covertness of these personality states, however, varies as a function of psychological motivation, current level of stress, culture, internal conflicts and dynamics, and emotional resilience. Sustained periods of identity disruption may occur when psychosocial pressures are severe and/or prolonged. In many possession-form cases of dissociative identity disorder, and in a small proportion of non-possession-form cases, manifestations of alternate identities are highly overt. Most individuals with non-possession-form dissociative identity disorder do not overtly display their discontinuity of identity for long periods of time; only a small minority present to clinical attention with observable alternation of identities. When alternate personality states are not directly observed, the disorder can be identified by two clusters of symptoms:

- sudden alterations or discontinuities in sense of self and sense of agency (Criterion A), and

- recurrent dissociative amnesias (Criterion B).

Criterion A symptoms are related to discontinuities of experience that can affect any aspect of an individual’s functioning. Individuals with dissociative identity disorder may report the feeling that they have suddenly become depersonalized observers of their “own” speech and actions, which they may feel powerless to stop (sense of self). Such individuals may also report perceptions of voices (e.g., a child’s voice; crying; the voice of a spiritual being). In some cases, voices are experienced as multiple, perplexing, independent thought streams over which the individual experiences no control.

Strong emotions, impulses, and even speech or other actions may suddenly emerge, without a sense of personal ownership or control (sense of agency). These emotions and impulses are frequently reported as ego-dystonic and puzzling. Attitudes, outlooks, and personal preferences (e.g., about food, activities, dress) may suddenly shift and then shift back. Individuals may report that their bodies feel different (e.g., like a small child, like the opposite gender, huge and muscular). Alterations in sense of self and loss of personal agency may be accompanied by a feeling that these attitudes, emotions, and behaviors—even one’s body—are “not mine” and/or are “not under my control.”

Although most Criterion A symptoms are subjective, many of these sudden discontinuities in speech, affect, and behavior can be witnessed by family, friends, or the clinician. Non-epileptic seizures and other conversion symptoms are prominent in some presentations of dissociative identity disorder, especially in some non-Western settings.

The dissociative amnesia of individuals with dissociative identity disorder manifests in three primary ways: as

- gaps in remote memory of personal life events (e.g., periods of childhood or adolescence; some important life events, such as the death of a grandparent, getting married, giving birth);

- lapses in dependable memory (e.g., of what happened today, of well-learned skills such as how to do their job, use a computer, read, drive); and

- discovery of evidence of their everyday actions and tasks that they do not recollect doing (e.g., finding unexplained objects in their shopping bags or among their possessions; finding perplexing writings or drawings that they must have created; discovering injuries; “coming to” in the midst of doing something).

- Dissociative fugues, wherein the person discovers dissociated travel, are common. Thus, individuals with dissociative identity disorder may report that they have suddenly found themselves at the beach, at work, in a nightclub, or somewhere at home (e.g., in the closet, on a bed or sofa, in the corner) with no memory of how they came to be there.

Amnesia in individuals with dissociative identity disorder is not limited to stressful or traumatic events; these individuals often cannot recall everyday events as well.

Individuals with dissociative identity disorder vary in their awareness and attitude toward their amnesias. It is common for these individuals to minimize their amnestic symptoms. Some of their amnestic behaviors may be apparent to others—as when these persons do not recall something they were witnessed to have done or said, when they cannot remember their own name, or when they do not recognize their spouse, children, or close friends.

Possession-form identities in dissociative identity disorder typically manifest as behaviors that appear as if a “spirit,” supernatural being, or outside person has taken control, such that the individual begins speaking or acting in a distinctly different manner. For example, an individual’s behavior may give the appearance that her identity has been replaced by the “ghost” of a girl who committed suicide in the same community years before, speaking and acting as though she were still alive. Or an individual may be “taken over” by a demon or deity, resulting in profound impairment, and demanding that the individual or a relative be punished for a past act, followed by more subtle periods of identity alteration. However, the majority of possession states around the world are normal, usually part of spiritual practice, and do not meet criteria for dissociative identity disorder. The identities that arise during possession-form dissociative identity disorder present recurrently, are unwanted and involuntary, cause clinically significant distress or impairment (Criterion C), and are not a normal part of a broadly accepted cultural or religious practice (Criterion D).

The American Psychological Association, DSM-5

Symptoms in the DSM-5

The key characteristic of Dissociative Identity Disorder is the presence of at least two distinct personality states (described in some cultures as an experience of “possession”). The presence of reoccurring periods of amnesia is the next most important characteristic, sometimes referred to as recurrent lapses in memory which go beyond ordinary forgetting.

The remaining diagnostic criteria require symptoms to cause distress and/or impaired functioning in at least one area of life, and state that DID can only be diagnosed if no other condition provides a better explanation for symptoms.

A mix of secondary symptoms are found in DID, particularly those caused by the passive influence of alters intruding into awareness, but no single secondary symptom is present in everyone with Dissociative Identity Disorder, and these do not form part of the diagnostic criteria.

Alters are only overt (obvious) in a small minority of people with DID in clinical situations. A change introduced in the DSM-5 makes it possible to diagnose DID without the diagnosing clinician directly observing a switch between alters: instead, DID can be diagnosed if the person self-reports their presence and effects, or if another person describes observing a switch between alters.

Sense of Self and Agency

Attitudes, outlooks and personal preferences like preferred foods or clothes may change suddenly and inexplicably, and then change back again. This happens because alter personalities have different attitudes, outlooks and preferences, so a very sudden change without explanation occurs when an alter has either taken control or is strongly influencing the person. When that alter is no longer active, everything changes back (until the next time the same alter is active). During these times, a person may find have bought clothes they would never choose to wear, or a very outgoing person may suddenly become shy and introverted with no apparent reason.

Discontinuity in a person’s sense of agency means not feeling in control of, or as if you don’t “own” your feelings, thoughts or actions. For example, experiencing thoughts, feelings or actions that seem as if they are “not mine” or belong to someone else. This is not the delusional belief that they belong to an outside person; it is the perception that their own speech, thoughts, and/or behavior do not feel like they belong to them and may make no sense to them. Emotions and impulses are often described as puzzling to the person.

A person with DID may also experience a fully dissociated intrusion, and may say things like:

- I have no control; I watch what happens, but can’t stop it.

- I find myself “coming to” in the downtown area where I live, but I won’t remember where I parked the car.

- I have found myself crying uncontrollably and sucking my thumb, but I can’t explain why.

- Sometimes I’ve had people call me by a name I don’t recognize, and I don’t know who they are.

The combined changes in “sense of self” and “sense of agency” can cause a person to find themselves feeling like they are watching passively while someone else controls their body; they hear themselves speaking words they would never normally speak and that may not make sense to them, and which they are powerless to stop.

Some people describe this combined change of “sense of self” and “sense of agency” as feeling like an experience of possession, in a non-religious sense, or having their body “hijacked”. A person with DID may find that their body feels totally different during this time (e.g., like a small child, the opposite gender, huge and muscular), or may feel as if they are suddenly younger or older.

Recurrent Amnesia: Criterion B

In DID, total amnesia for the actions of alter personalities is not necessary - it is possible for a person to be aware of many of their actions at the time, known as co-consciousness, or remember some of what happened later. If a person does have total amnesia, the changes in a person’s speech, mood and behavior may be witnessed by others and reported back to them, but they may deny this “odd behavior” because they have no memory of it, which can lead others to incorrectly assume they are repeatedly lying.

2025, Dissociative Identity Disorder (formerly Multiple Personality Disorder)

Someone who has yet to be diagnosed may not recognize their internal landscape as being composed of a cast of alternate identities; instead, the person might describe “a persistent quality of feeling like ‘not me,’” said Amy Dierberger, a psychologist who treats people with DID. Patients may say they feel as if they have different “parts, parts inside, aspects, facets, ways of being, voices, multiples, selves, ages of me,” according to one common treatment guideline. Sometimes these parts or voices argue, converse, comfort, or urge a person to commit suicide. Another frequent symptom is “losing time.” Patients realize they have made purchases or gone places they don’t remember.

Clinicians now understand that all of a DID patient’s parts put together constitute a single personality. “There are different senses of self with different attributes, but there aren’t lots of people in one body,” explained Richard J. Loewenstein, another expert in dissociation. “You’re all aspects of a single human being and a single mind.”

The condition is both “incredible” and requires treatment that is “very unexciting,” Dierberger said. Talk therapy with a professional trained in dissociation is considered the gold standard. While a person’s dissociative proclivities may never fully resolve, therapists believe that if a patient deliberately tries to connect with the parts of the self in therapy and works through their traumatic memories with each one, over time the sense of being made up of separate people may fade. Eventually, some or all of the parts may begin to “fuse” together into a cohesive sense of self. “Everything we do,” said Loewenstein, “is unification.” Underlying the treatment is a fundamental medical understanding that experiencing multiple personalities in a single body is a symptom of mental illness.

Lizzie Feidelson, 2021, Meet My Multiple Mes

Contrast: Plurality and Internal Family Systems’s notions of nondisordered multiplicity (beyond and within a single self, respectively)

See also: DID, Comparison of Frameworks