The Theory of Structural Dissociation (TOSD) is a theory for how trauma and dissociative disorders develop.

In children, TOSD postulates that children have a number of unintegrated ego states. As children develop their identity in early childhood, these ego states integrate to form a single, coherent sense of self. If this process is interrupted by trauma, then these ego states may dissociate from each other instead of integrating. This is an adaptation to the unpredictable situations common to trauma, and it allows the person to survive by isolating trauma from normal consciousness.

In adults, TOSD postulates that when a person fails to integrate traumatic material, that material becomes contained by a dissociated part of the person’s pre-trauma personality.

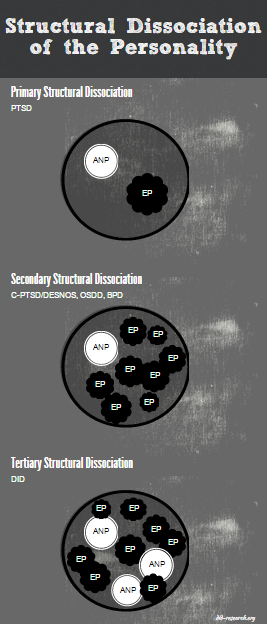

In either case, the resulting dissociated parts of self are often labelled as either Emotional Parts (EPs) or Apparently Normal Parts (ANPs) of the personality.

- EPs contain traumatic material and emotions. They may intrude on consciousness in the form of flashbacks.

- ANPs focus on daily life tasks and survival. They may lack knowledge of the trauma or otherwise experience losses in function.

Different conditions are theorized to have different numbers of EPs and ANPs; only DID is believed to have a system with more than one ANP in the original theory.

Excerpts from the Original Paper

Many traumatized individuals alternate between re-experiencing their trauma and being detached from, or even relatively unaware of the trauma and its effects. This alternating pattern has been noted for more than a century by students of psychotraumatology, who have observed that it can ensue after different degrees and kinds of traumatization. It is characteristic of posttraumatic stress disorder, disorder of extreme stress, and many cases of trauma-related dissociative disorders.

At first sight one may be inclined to conceptualize detachment from trauma and re-experiencing of trauma as mental states. However, on closer scrutiny it becomes apparent that in both cases a range or cluster of states rather than a singular state is involved. For example, being detached from trauma does not itself exclude being joyful, ashamed, sexually aroused, or curious at times, and re-experiencing trauma can encompass states such as fleeing, freezing, and being in pain or being analgesic.

In its primary form this dissociation is between the defensive system on one hand, and the systems that involve managing daily life and survival of the species on the other hand.

Background

In a little known but important work, Myers (1940) described primary structural dissociation in terms of a dividedness between the “apparently normal” personality and the “emotional” personality. Studying acutely traumatized World War I combat soldiers, Myers observed that the “emotional” personality (EP) recurrently suffers vivid sensorimotor experiences charged with painful affects which, at least subjectively, closely match the original trauma. Thus the EP is stuck in the traumatic experience that persistently fails to become a narrative memory of the trauma. The “apparently normal” personality (ANP), on the other hand, is associated with avoidance of the traumatic memories, detachment, numbing, and partial or complete amnesia.

Both ANP and EP in fact involve differences with respect to a wide range of psychobiological variables. For example, clinical observations indicate that they are both associated with a differential sense of self, and findings from experimental research into DID suggest that they display differential psychobiological responses to trauma memories, including a different sense of self, as well as to preconsciously processed threatening stimuli.

An essential component of integration is personification. Personification denotes the mental actions that range from relating synthesized material to one’s general sense of self, which thus should become regularly adapted through synthetic actions, to becoming consciously aware of the implications of a personal experience for one’s whole life, giving one’s history and sense of self a continuity. To follow up the example, in the act of personification, traumatized individuals become consciously aware that the threat strikes them personally. The result is a sense of ownership of personal experience and events (“I am threatened”).

As countless clinical observations suggest, and as recent studies have documented, overwhelming events can interfere with these integrative mental actions. When personification fails, conscious awareness of the synthesized event will remain factual knowledge that does not seem to pertain to oneis self. In the terms of Wheeler, Stuss, and Tulving (1997), the synthesized material will be noetic (personal experiences that seem unrelated to self), not autonoetic (personal experiences that are integrated with awareness of self as part of the experience). Thus a traumatized individual may say: “I know my life was threatened, but it feels as if it happened to somebody else.”

Within far wider windows of time and events, personification yields an integrated, thus relatively context-independent sense of self. When personification fails, the development of a coherent sense of personal existence in a framework of the past, the present, and the future is compromised. In order to act adaptively in the present, it is necessary for personification of current experience to be based on the integration of one’s (entire) past history.

We concur with Myers (1940) that the failure to integrate traumatic experiences basically yields a structural dissociation of the premorbid personality into two mental systems. This primary structural dissociation involves the EP that is essentially associated with re-experiencing the trauma, and the ANP that has failed to integrate the traumatic experience, and that engages in matters of daily life.

Emotional Parts

The EP is a manifestation of a more or less complex mental system that essentially involves traumatic memories. When traumatized individuals remain as EP, these memories are autonoetic for the EP, but not for the ANP. The memories can represent kernel aspects of the trauma, a complete overwhelming event, or series of such events, and are usually associated with a different image of the body and a rudimentary or more evolved separate sense of self. Thus the EP range in forms from reexperiencing unintegrated (aspects of) trauma in cases of acute and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), to traumatized dissociative parts of the personality in dissociative identity disorder (DID).

When the EP is activated, the patient in that state tends to lose access to a range of memories that are readily available for the ANP. The lost memories typically involve episodic memories (personified memories of personal experiences), but may also include semantic memories (factual knowledge) and even procedural memories (e.g., memories for skills and specific kinds of associations among various stimuli as a result of classical conditioning).

The EP typically displays defensive motor behaviors, in particular in response to “triggers” i.e. classically conditioned, trauma-related stimuli. For example, in this condition, the patient may curl up in her chair, and remain largely immobile and silent. She may also hide behind a chair or in a corner. However, when feeling relatively safe, she may be more verbal and mobile. Thus in cases of childhood abuse, the EP with the identity of a child can occasionally display behaviors such as childlike playfulness.

The field of consciousness of the EP tends to be highly restricted to the trauma as such and to trauma-related affairs. When EPs have evolved, as happens in DID, they may additionally be focused on matters of the current world that fit their experience and identity. In these cases, their procedural, semantic, and episodic memories have been extended to some degree. However, while the EP has synthesized and personified (aspects of) the trauma into its limited range of memories, thus into the part of the personality it represents, it has failed to integrate current reality to a sufficient extent. This leaves the EP ultimately unable to adapt to present reality.

Apparently Normal Parts

The “apparently normal” part of the personality. Traumatized individuals fail to sufficiently integrate current reality — normal life — as EP. As ANP they have failed to integrate the trauma, either partially or fully, and tend to be more or less engaged in normal life. The ANP is predominantly marked by a range of losses or so-called negative dissociative symptoms, such as a degree of amnesia for the trauma and anesthesia of various sensory modalities. The ANP is also characterized by a lack of personification, both with respect to the traumatic memory and with the EP. That is, the ANP has integrated neither the traumatic memory, nor the mental system that is associated with this memory. To the extent that the patient as ANP is informed about the trauma and about the EP, this knowledge remains noetic, and the relevant memories semantic, i.e., lacking personification.

Intrusions of the EP, especially the traumatic memory that is associated with this part of the personality, interfere with apparent normality. When in a dispositional state, traumatic memories and other trauma-related mental phenomena are usually not a hindrance. However, when fully reactivated, they, like harmful “parasites of the mind,” may overgrow consciousness. These intrusive, hence positive, dissociative symptoms may consume a considerable amount of time and energy, partly reproducing the time-line of the overwhelming event. The re-experiencing usually follows a fixed course of events and responses, and cannot be interrupted, or only with excessive effort. The ANP can also be intruded by complete traumatic memories or by aspects of them, such as a particular sensation or motor response. The ANP may ultimately become deactivated upon the activation of the EP, a phenomenon that results in the ANP’s amnesia for the episode.

Apart from traumatic memories, other features of the EP can intrude the ANP as well. Examples include hearing the voice of the EP and being subjected to intentional physical movements of the EP. The ANP often fears these symptoms due to a range of variables such as a lack of insight into the nature of the phenomena, a lack of control over them, their association with traumatic memories, and their specific qualities such as a crying or angry voice, and the nature of the messages of the voice.

Although we have identified intrusions as positive symptoms, the content of the intrusions may also involve losses. Thus negative symptoms, such as inhibited movements, and positive symptoms, such as pain, or both, may be present. The complete deactivation of the ANP upon reactivation of the EP can also be described as a combination of two extreme negative (deactivation of ANP) and positive symptoms (activation of EP), respectively.

Summary of EPs and ANPs

The EP is dedicated to the survival of “predatory” threat. In our analysis, EPs essentially are manifestations of action systems: primarly the one that controls defense in the face of threat — foremost threat to the integrity of the body by a person — and potentially also the one that controls attachment to caretakers. Both systems serve survival interests and strongly influence what the patient remaining as EP is likely to sense, perceive, feel, think, recall, and do.

The ANP is dedicated to managing daily life and to survival of the species. Clinical observations suggest that while EPs are essentially dedicated to functions that serve the survival of the individual when exposed to major threat, the functions of the ANP are to perform daily tasks necessary to living, as well as tasks that serve the survival of the species.

TOSD in Children

So far, we have assumed that the personality prior to traumatization developed as a relatively integrated mental system. However, with young children such is hardly the case. The first years of life are important in laying the groundwork of a personality organization that is rather cohesive across contextual variables, such as place, time, and state. This developmental process can be threatened by the occurrence of traumatic experiences during the formative years.

Trauma may interfere with this developmental process: the child will have difficulty integrating action systems, and constructing cohesive autonoetic consciousness and episodic memory. As Perry and his colleagues have argued, repeated activation of specific trauma-related states, or, in our terms, EPs, leads to neurobiological “hard-wiring” of the brain. In particular, the wiring of the developing brain seems to be dependent on the child’s life experiences, with the first six years of life as a critical period. Because young children have not yet been able to develop a personality structure that allows for the integration of very stressful experiences, early and chronic childhood traumatization can shape the mind and the brain in ways that promote state-dependent functioning or functioning that is dependent on dissociative parts of the personality.

Traumatized young children may not have developed a relatively integrated personality prior to the onset of trauma, so in terms of the present theory, the emergent structural dissociation of their personality will basically consist of at least one or more ANPs and one or more EPs. Our clinical observations indeed suggest that even in cases of extreme tertiary structural dissociation of the personality, i.e., DID, the basic division is between parts of the personality that manage daily life and that promote survival of the species (ANPs), and parts that are associated with survival of the individual in the face of (perceived) major threat (EPs). Because some patients with DID display strongly developed — that is, emancipated — ANPs and EPs, and because some may have learned to control the switching between these mental systems in the course of treatment, these patients are ideal subjects for studying the psychobiological features of ANP and EP.

Ellert Nijenhuis, Onno van der Hart, & Kathy Steele, 2004, Trauma-related Structural Dissociation of the Personality

The Plural Community and TOSD

The Plural Community has a love-hate relationship with the Theory of Structural Dissociation. It is normalizing to understand everyone is born with parts, and to learn that trauma interferes with normal integration as part of development relieves some of the shame Plurals carry by default. The Plural community appreciates these revelations being documented.

But there is misattunement in structural dissociation’s break from the traditional view of multiplicity, which results in the new (debated) assumption of one personality (divided into parts), which attempted to dismiss four millennia of conceptualizing more-than-one personality, ultimately attempting to shift the concept from “multiplicity” to “divisibility” in only two decades.

This one aspect of structural dissociation feels incongruent with lived experience, and causes miscommunication when people are using the same words for different things, This is still being reviewed, with Steele (2021) returning to more ego state language and van der Hart (2021) shifting to “degrees” of dissociation and reporting that “dissociative parts of the personality may comprise any number of psychobiological states, which implies that labeling them ego-states or self-states is giving them a too low degree of reality.”

Emily M Christensen, 2022, The online community: DID and plurality